How can we increase the effectiveness of mass dog vaccination campaigns?

- Community News

- Dog vaccination

Mass dog vaccination is widely acknowledged as the most effective means of controlling canine rabies. Annual vaccination campaigns should aim to reach >70% of the dog population in order to achieve eventual elimination of rabies from an area, and this target coverage has repeatedly been shown to be attainable. But, how long does it take to achieve elimination?

While high vaccination coverage is clearly important, other factors, such as gaps in coverage, dog movement patterns, and local rabies awareness, could also influence control efforts. Identifying these factors is crucial for the design of effective elimination programmes.

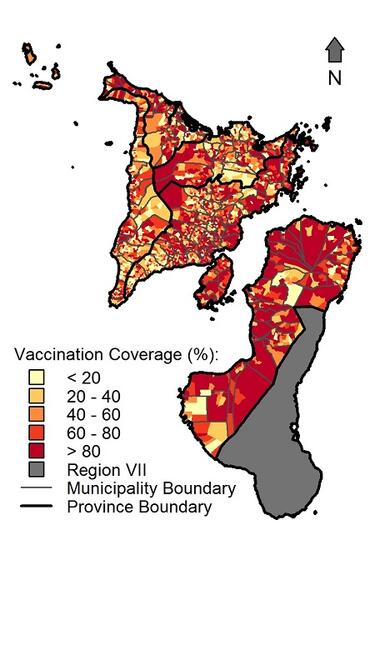

Annual dog vaccination campaigns are ongoing in Region VI of the Philippines (Western Visayas) as part of a rabies elimination demonstration project coordinated by WHO and funded by the Gates Foundation. A household survey in the region (conducted by the Philippines Department of Health with logistical support from the Animal Welfare Coalition and the University of Glasgow) collected data on vaccination coverage and on how often and how far people moved their dogs. These data suggest that the 2010-2012 campaigns were very successful – average coverages achieved each year exceeded 70% of the dog population. However, there was evidence of considerable spatial variation in this coverage, which could prevent elimination by allowing the virus to persist in poorly vaccinated areas. Dogs moved frequently with their owners, particularly between nearby villages or municipalities, but with a surprising number of movements occurring over much longer distances – hundreds of dogs are estimated to arrive in the region annually from other countries.

In a recent study, we examined the effects of uneven vaccination coverage and dog movements on the chances of rabies elimination in Region VI using a model of rabies transmission. The model simulated rabies spread in the region, incorporating realistic patterns of vaccination coverage and dog movement derived from the survey. These simulations suggested that, despite the high overall vaccination coverage, the probability of rabies elimination was much lower than if the same average coverage had been applied equally everywhere. Three more similarly variable campaigns could be required to eliminate rabies from the region with high probability; a doubling of vaccination effort that would likely have been unnecessary had coverage been even.

An exploration of potential improvements to the campaigns suggested that halving the variation in coverage in future campaigns without increasing overall coverage would eliminate rabies more rapidly than a 10% increase in overall coverage. Model outputs also suggested that dog movements (even at higher rates than those observed in Region VI) do not have negative impacts on campaign effectiveness whilst rabies remains endemic.

These results provide practical suggestions to reduce the time taken for mass dog vaccination campaigns to eliminate endemic rabies. To ensure rapid elimination, reduce programme costs and minimise the risk of further human and canine rabies casualties, a homogeneously high coverage across the control area is necessary. However, uneven coverage is likely to be a common problem in rabies control programmes. Gaps in coverage, even at the village/neighbourhood level, can harbour disease, so ensuring that vaccination is easily accessible to all is critical. Human-mediated dog movements do not appear to reduce campaign effectiveness in an endemic rabies setting, so imposing restrictions on dog movements would be an unnecessary drain on limited resources prior to elimination. However, given the estimated high frequency of long-distance dog movements, measures to prevent reintroduction into rabies-free areas will be required post-elimination.

Contributed by Elaine Ferguson of the University of Glasgow, the lead author of the study. The paper ’Heterogeneity in the spread and control of infectious disease: consequences for the elimination of canine rabies’ was published in Scientific Reports in December 2015.