December 2025 Champion in Action: Jacques Barrat

From the mountains of the Pyrenees to the fox-dense forests of eastern France, and abroad, mainly in Europe and Africa, Jacques Barrat has worked towards shaping modern rabies control methods. However, for him it was never planned, as he states: “I was organically led to rabies… and never came out of it.” In our December edition of Champions in Action, we want to showcase Jacques' remarkable career and how he unexpectedly started with rabies work. He shares some of his memorable moments in the field, and some wisdom for future veterinarians worldwide.

How did your journey in veterinary medicine begin and how did it lead you to rabies?

In France, veterinary studies are very different. You do not start at university. You prepare for years, pass a competitive exam, and if you get in, you are almost sure to finish Doctor in Veterinary Medicine. I entered the National Veterinary School of Toulouse in 1972. After graduating, I spent 3 years as an assistant in the botany and animal feeding laboratory, analyzing the diets of Pyrenean brown bears and mouflons in Corbières and the Alps. This professional life took me outdoors, looking for plants to establish the reference collections for these studies. Luckily, I managed to survive this pleasant hardship!

Everything changed when I needed to complete my military service. I contacted a lab that worked on rabies and fox ecology because I wanted to learn how to use radio tracking. I joined that lab, and that was it! From 1980 onwards, I never left the field. Soon after, I became head of the rabies diagnosis service and also worked on wildlife diseases, virology and animal experimentation.

What was the rabies situation in France when you started all those years ago?

Rabies had entered France in 1968 from Germany and was spreading through fox populations. When I arrived, in the infected area, the rule was simple: rabies means foxes; no foxes, no rabies. Fox rabies control was based on fox culling. There were government bounties and widespread culling. Some years later we proved that this method was “strictly inefficient.” At the same time, Switzerland had begun experimenting on oral vaccination in the field using chicken heads containing vaccine blisters. In 1986, the Northeastern quarter of France was infected. France began oral vaccination campaigns then: it was a scientific adventure.

The team first had to confirm through experiments that the oral vaccines protected the red fox and were safe for foxes and for non-target wildlife that could eat the baits (foxes only ate around 10%). We tested multiple strains, including SAD, SAG, and VRG (a recombinant vaccine), and also studied the immune response of cubs and the possible interference of maternal immunity on cub’s immunization. Baiting was distributed from helicopter during spring and autumn campaigns. The largest campaign covered up to 100 000 km² in the Northeast. It was expensive, but in the end, up to 80% of the fox population was vaccinated, and rabies cases in domestic animals and foxes disappeared. France became officially free of terrestrial rabies in 2001, with the last fox-linked case (a cat) detected in 1998.

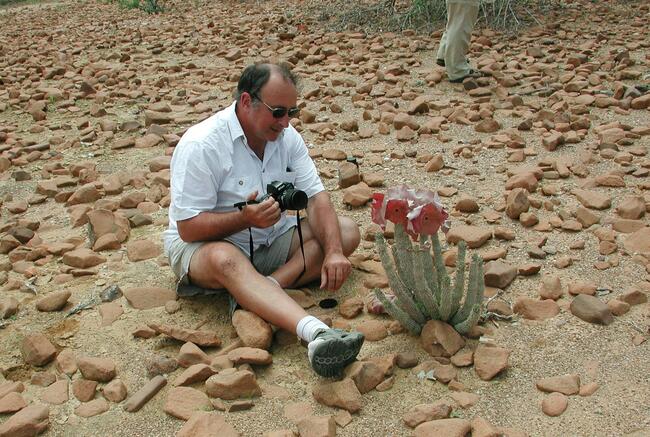

You have also carried out extensive international work. What stands out most from your time abroad?

I helped to establish the Southern and Eastern African Rabies Group (SEARG), collaborated with leading rabies scientists and supported training program in rabies diagnosis and sampling. My most difficult experience, however, was to discover the big discrepancies that exist between countries concerning how they manage human rabies. In some countries I experienced monopolies on the importation of human vaccines. In others, there was a complete absence of palliative treatment during the clinical phase of the disease. While in rural Africa, with far fewer resources, people at least tried to help ease the pain of those infected. The difference was shocking, and it marked me deeply.

This experience really reinforced for me the power of individuals. You need one good person, a champion, at the right place to push forward. If you do not have that, you have routine, and routine leads to unnecessary deaths.

What do you consider your greatest professional challenge?

Convincing people to stop killing foxes. It took years. Internationally, I found that fighting political and economic barriers is harder than fighting rabies itself.

What advice would you give young veterinarians today?

I am only half joking when I say: You will have a lot of fun with rabies. But:

- Private practice is important, however, it is not the only path.

- Large-animal and rural medicine teach creativity and resourcefulness.

- Wildlife and public health are wonderful careers if you want adventure.

- Just follow your curiosity, you have the choice: private practice, wildlife study, epidemiology, field research and teaching are all full of joy and meaning.

Once you fall into rabies, you cannot escape it. But you meet very interesting people along the way.

After everything, what keeps you passionate about rabies elimination?

It is simple: Rabies is completely preventable. So, any death is unacceptable. If you can do something, even small, you must. And if you meet the right people, you can change everything.

The Communities Against Rabies initiative is supported by Battersea Dogs and Cats Home.